When I was younger, time seemed linear.

Change seemed directional and inevitable. My generation seemed more open-minded than our parents generation. Same-sex marriage went from illegal to legal in some states, to nationally legal. Barriers between people and places felt like they were naturally dissolving. Social media platforms made the world seem small. I could log in to Facebook and chat with friends across the globe. We could keep up with each other's lives.

Google had their "Don't Be Evil" philosophy and folks going to work in jeans and hoodies seemed so much more authentic than the awkward fitting suits normalized by the generations before. It seemed obvious that traditional hierarchies and formality were fading away in place of more authentically connected work environments.

The changes were not only coming to the business world, empowerment was spreading to the people. The Arab Spring showed us the toppling of dictators on social media in real-time. Information and connection were liberation.

Everything was pointing towards a more open, connected, collaborative world. It seemed inevitable that authentic voices would naturally rise and oppressive systems would crumble.

Perhaps it was my rose-colored glasses or maybe just youth itself, but change seemed linear.

As I continued accumulating trips around the sun, the trajectory I'd believed in began to fracture. My own generation, which had felt so uniformly progressive, started fragmenting politically. The very same tech companies that symbolized authenticity and connection became sources of division and distrust. The platforms used to topple dictators were now being used to spread misinformation and polarize communities. Progress, it seemed, was not a straight line but something else entirely.

The Ancient Wisdom of Cycles

The ouroboros is a Greek symbol of a snake devouring it's own tail. This ring-shaped serpent is found in countless cultures, each recognizing something fundamental about the nature of time and existence.

Like many things Greek, this symbol originates in Egypt. The sun god Ra took nightly journeys to the underworld, protected by his serpent Mehen wrapped around him. The ouroboros is often depicted with dark scales on one side and light on the other, representing the duality of existence. Or simply, night and day.

In some versions, for every hour Ra spends in the underworld, the serpent consumes an hour's worth of dark scales, representing the cycle of time. By consuming itself, the serpent renews itself in daily cycles of death and rebirth. For the ancient Egyptians destruction and creation were not opposing ideas, just different phases of a continuous cycle.

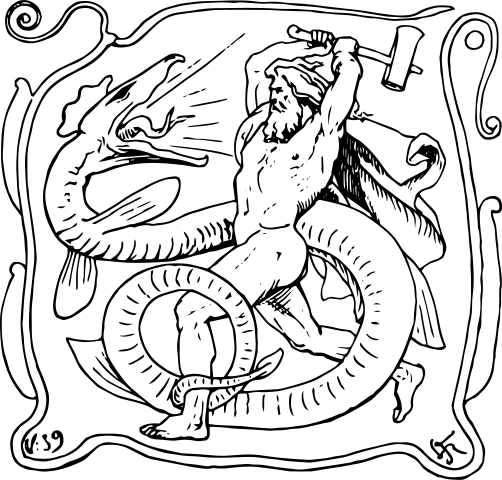

The Norse had their own version. Jörmungandr was one of three children born to Loki alongside the wolf Fenrir and Hel, ruler of the underworld. Fearing their power, Odin cast Jörmungandr into the great ocean encircling Midgard, our human realm. Jörmungandr grew until he encircled the entire world, grasping his own tail in his mouth.

If Jörmungandr lets go of his tail, Ragnarök, the end of the world, begins. A prophecy tells that Thor and Jörmungandr are destined to kill each other, with Thor slaying the serpent but having strength to take only nine steps before falling. Destroying the ouroboros brings the end of the world and the death of humanity's greatest hero.

Cycles aren't just patterns we observe. They're fundamental structures holding reality together.

The Inevitability of Cycles

Cycles persist because we cannot have wealth without illth. The 19th-century writer John Ruskin coined these brilliant terms: "wealth" encompasses all accumulated changes beneficial to humanity and supportive of life itself, while "illth" represents all the detrimental accumulations that poison our systems and relationships.

Every innovation carries unintended consequences. The internet connected us globally while fragmenting our attention and eroding privacy. Suburban expansion gave families homes and yards while creating car dependency and social isolation. Even personal growth can follow this pattern. Gained expertise often means narrowing perspective and stress often accumulates with success.

The cycle turns when illth outweighs wealth. Like a forest that accumulates deadwood until a lightning strike creates a cleansing fire, our systems build up illth until correction becomes inevitable. We see this clearly in economic cycles. Ray Dalio, in Principles for Navigating Big Debt Crises, illustrates how companies accumulate debt alongside growth until the debt burden forces a reckoning. During good times, businesses focus on tomorrow's projected profits rather than today's margins. Banks lend liberally. Competition drives over-leveraging. Eventually, defaults begin. Credit becomes scarce. Layoffs and hiring freezes follow. The correction isn't a failure of the system; it's the system working as it must. Winter clears away autumn's decay. The bear market purges the bull market's excess.

The duration of cycles remains unpredictable, and they tend to reach euphoric highs before crashing. This timing uncertainty adds to our blindness. People entering the workforce during growth think expansion is normal; those entering during contraction believe scarcity is permanent. For each generation, one phase looms larger than the other.

Modern Cycles in Action

Even in the past decade of tech, we find micro-cycles. Every few years, people proclaim design is dead or product management is obsolete, only to be followed by massive growth in those fields. When voice interfaces emerged in the mid-2010s, many declared visual interfaces dead. Instead, we saw an explosion of visual interface innovation alongside voice and sensor technologies. Today, we hear the same about AI, all interfaces will be chatbots and again, designers will become obsolete.

Since 2023, the tech world has endured multiple rounds of layoffs and hiring freezes. Some leave the industry entirely, convinced AI means fewer jobs forever. But it's more likely the job is evolving, as it always has.

We're also cycling through broader patterns. Recently, Jony Ive reflected on arriving in 1990s San Francisco from the UK, finding it filled with optimism and people wanting to change the world for the better. Today, he observed, it's more about money and power. This too may be a cycle going from idealism to cynicism and likely back again.

Tied to cycles of growth and decline, we have cycles of greed and generosity. Today's era seems to favor a form of avarice. Despite unprecedented wealth, those with less are seen as parasites rather than humans needing support. Not long ago, Bill Gates and Warren Buffett championed pledging away fortunes. Recently, Peter Thiel proclaimed on a podcast that philanthropy should be viewed with suspicion suggesting that the wealthy give away money for nefarious reasons. Generosity, once a virtue, becomes viewed as vice.

In hard times, we rely on communities. Perhaps long prosperity has pushed us toward individualism, as more people feel "self-sufficient." Or perhaps individual growth has become so demanding and alienating that we're losing the capacity to care for others. Whatever the cause, this too is just another phase. Something is always brewing below the surface to bring the next turn.

Beyond Circles: The Spiral

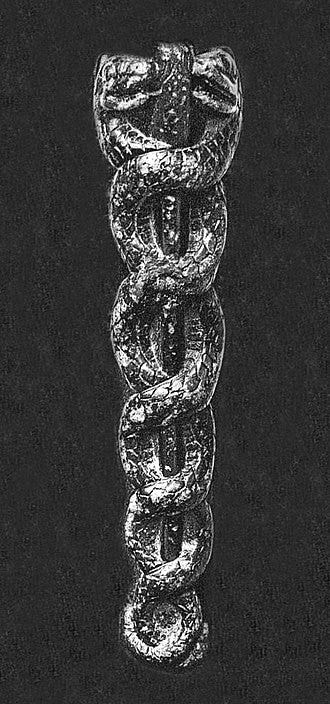

But these snake symbols aren't all circular. Going back to the Greeks, Hermes carried the caduceus—a staff with two intertwined serpents ascending upward, topped with wings. Legend says Hermes came upon two snakes engaged in deadly combat. Being the diplomat he is, he threw his staff between them to separate the fight. Instead of continuing to battle, they wound themselves around the staff into a harmonious spiral.

The first known staff with intertwined serpents comes from the Sumerian god Ningishzida, also associated with the underworld and transformation. It symbolized not just cycles but transformation and fertility. Not just going around, but going somewhere.

Linear time tells us that wars end and then peace arrives, inevitable and permanent. Cyclical time tells us there are times of war and times of peace, endlessly alternating. But spiral time tells us there are times of prosperity and conflict, yet the form may evolve. Cyclical thinking assumes conflict must mean war and violence. Spiral thinking says it doesn't have to look the same way each time.

Transforming Illth into Wealth

What if we could work with wealth and illth differently? Cyclical thinking tells us to brace for impact. That accumulation of illth leads to inevitable collapse. Spiral thinking suggests something more nuanced: we can consciously metabolize illth into wealth.

Consider how nature handles this in spirals rather than circles. Trees transform their own fallen leaves into soil, converting yesterday's illth into tomorrow's wealth. Each ring in the trunk is not just another year, but an integration of all previous years. The spiral moves upwards because it transforms instead of simply repeating.

In human systems, this might mean actively composting our illth rather than letting it accumulate to toxic levels. Tech companies recognizing their products' attention-fragmenting effects may start designing for digital wellbeing. Economic systems can evolve to pricing in environmental costs rather than externalizing them. Organizations could regularly prune bureaucracy before it chokes innovation.

When we shift from cyclical to spiral thinking, Ruskin's framework evolves. Instead of wealth and illth as fixed categories locked in inevitable cycles of accumulation and collapse, we see them as raw materials in ongoing transformation. The question becomes not "when will the illth overwhelm us?" but "how can we alchemize today's illth into tomorrow's wealth?"

Living in Spiral Time

Certain innovations excel in hard times. Certain opportunities only appear during struggle. After the 2008 crash, those who saw opportunity rather than just catastrophe found the investment opportunity of a lifetime. It's when we learn to do more with less. Risk aversion seems permanently etched into the culture—until it isn't. Eventually, the environment shifts, balance sheets strengthen, and the appetite for growth returns. But on the spiral, it's not the same growth as before.

Lets look at the current AI disruption. Linear thinking says: "AI will permanently eliminate millions of jobs." Cyclical thinking says: "This too shall pass, like every other technological disruption." Spiral thinking asks: "How do we transform this disruption into evolution? What new forms of human creativity emerge when machines handle routine tasks? How do we compost the illth of job displacement into the wealth of human flourishing?"

Fortunately and unfortunately, cycles don't end. They're baked into the fabric of creation. The ancients understood this better than modern societies. But we don't have to be passive passengers on the wheel. We can choose our relationship to time itself.

Will it be ouroboros consuming itself in an endless circle or the caduceus transforming conflict into harmony?

In a movie called The Edge with Alec Baldwin and Anthony Hopkins, the two find themselves stranded in the wilderness. At some point, Hopkin's character asks "Did you know you can make fire from ice? Did you know that could be done? Bob, can you think?"

Fire from ice... think.

Note on AI use: I wrote this piece with the assistance of AI, specifically Claude. I wrote most of the piece, but my ideas were scattered for a long-time with this one. Claude helped with research, iterating through different outlines, answering questions, some rephrasing and mostly helping me cut out the clutter.